The great Mughals of India who ruled the Subcontinent from 1527 to around 1803

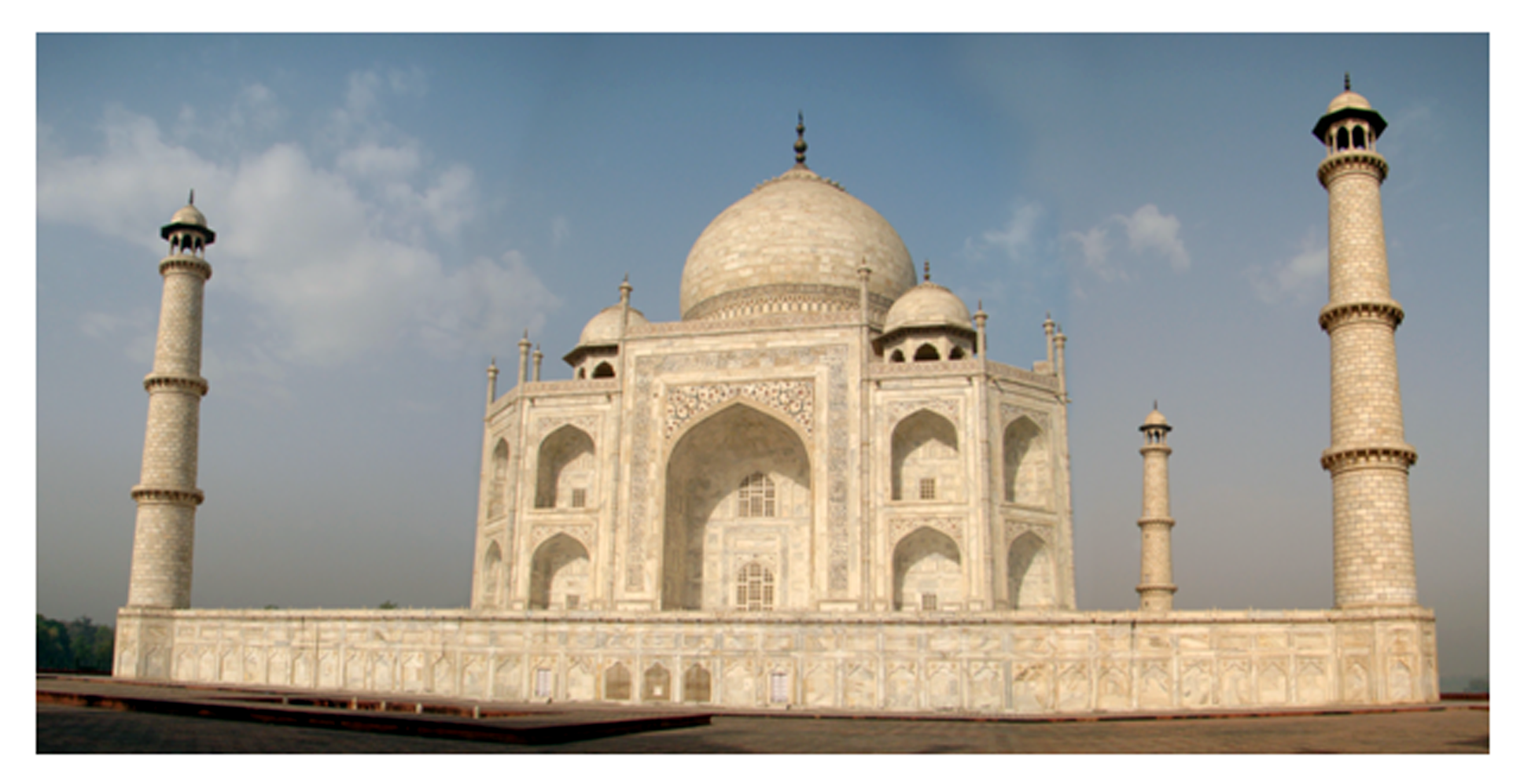

In common American usage, a mogul means a powerful or influential person (e.g. Hollywood mogul or media mogul.) However, few people would know that the word derives from the great Mughals of India who ruled the Subcontinent from 1527 to around 1803. The Mughal Empire extended from Kabul east to Dacca and from Kashmir to Hyderabad in the south. West of Kabul was the domain of the Persian Safavi empire that bordered and sometimes warred with the Ottoman Empire. In wealth and grandeur, the Mughal Empire probably outshone the other empires because there was a constant stream of people migrating to India from all parts of the Muslim world in search of a better life.

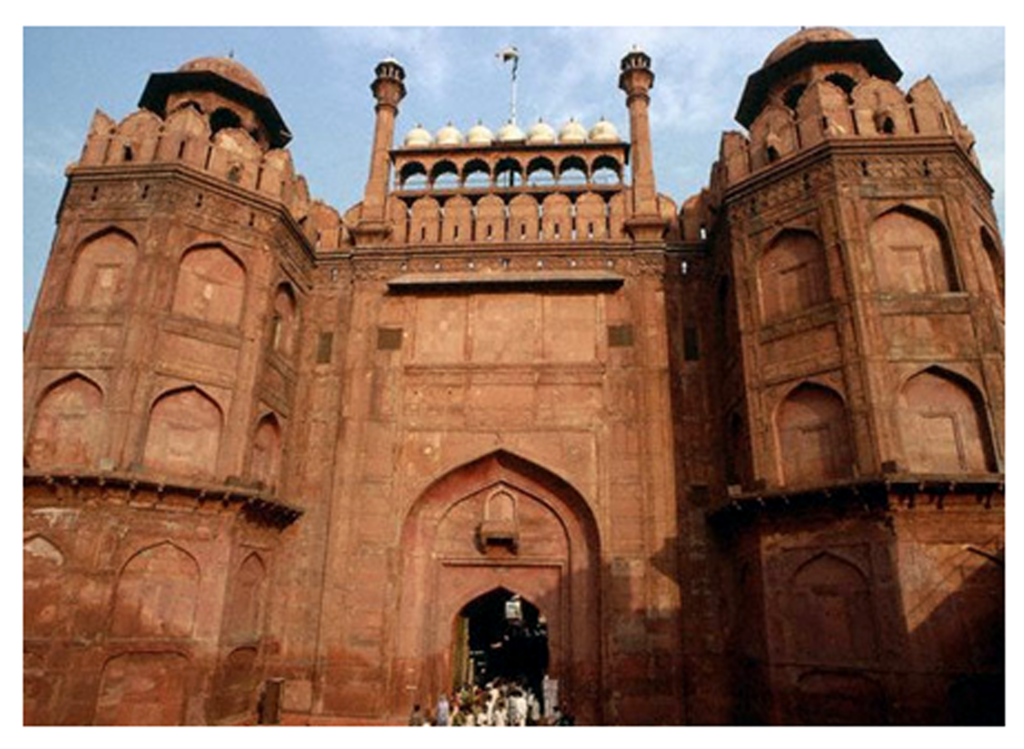

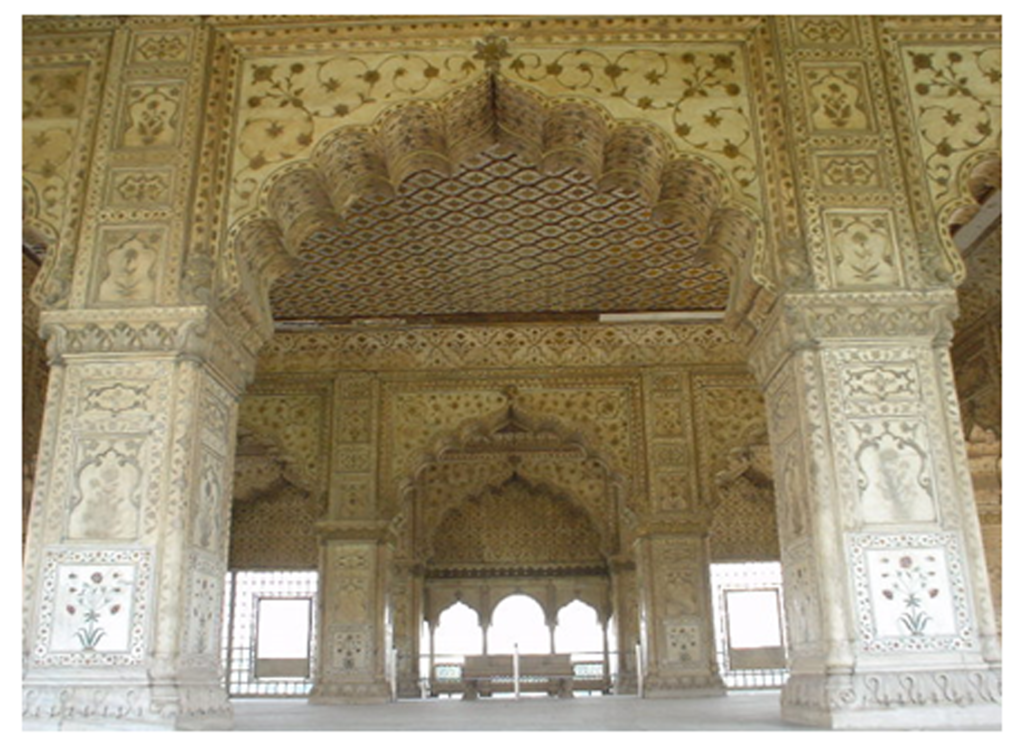

On my last visit to Delhi, in 2007, I wandered around one day in the few buildings from the Mughal times still left standing for the tourists at the Red Fort in Delhi. I gazed through the latticework of the great audience hall at the dry bed of the Jamuna River where cows were grazing.

This walled seat of Mughal power was then known as the Exalted Camp, or Urdu-e Moalla. The fort’s vast grounds were being well maintained with sculpted lawns, but long gone were the houses and mansions of the royal establishment that one surrounded it. They were first vandalized, then destroyed by the British Colonists in their zeal to terrorize the population in the aftermath of the 1857 war of independence.

I was never much of a fan of the Mughals, and had not found many personalities to admire in the historical accounts of their times. They, as with all humans, were products of their times. They did what they did because that was the thing to do. Babur, who came to India from his native Ferghana Valley in Uzbekistan and founded his empire, was great as a writer and chronicler of his exploits in his Tuzuk-e Babari, a classic in memoir writing that still remains a terrific read today. Not much to savor or cherish in the works of Humayun, who, though born in the greater India, still had central Asia in his veins. He didn’t take long to lose the empire he had inherited from Babur who literally gave his life so his son would live: Contemporary accounts report a story which has Babur, at around age 46, circling the bed of a severely ill Humayun, and praying that God may take his life and give it to his son. Babur died a few days later, but not before seeing his son recover.

A view of the royal palace inside the Red Fort

Humayun was driven out of India by an Afghan warrior, Sher Shah Suri, who wins high praise from modern historians for his administrative innovations and for his construction of a road connecting central India to Calcutta. But Humayun was lucky. He lived in exile in Iran for a few years, won the confidence of the ruling Safavi king, who gave him an army to go back to India and take back his empire. Again to his good luck, Sher Shah Suri died on his way to confront Humayun’s forces. Humayun himself was not long for this world, as the king died a year later when he fell down the steps of his library, his mind thoroughly addled with opium.

Humayun’s son, Akbar, was the one who truly settled down to claim all of India as his own, and proceeded to harmonize his Muslim baggage with the Indian realities. A syncretist movement, at times quite violent in the south of the country, had been under way for some time. Akbar actively encouraged popular tendencies among Muslim leaders to shed Islamic scholars hardline interpretations of the Quran and the Prophetic traditions. A composite, Persianate common culture had begun to prevail in most of the north and parts of southern India. The fourth Mughal emperor, Jahangir, was Akbar’s son by a Hindu wife, carried on his father’s policies although restrained by the realities of the power wielded by the guardians of a purist Islam, those who harbored fears that the Muslim communities would be absorbed by a deceptively tolerant Vedic thought and culture. They fought to erect high boundary walls between religions.

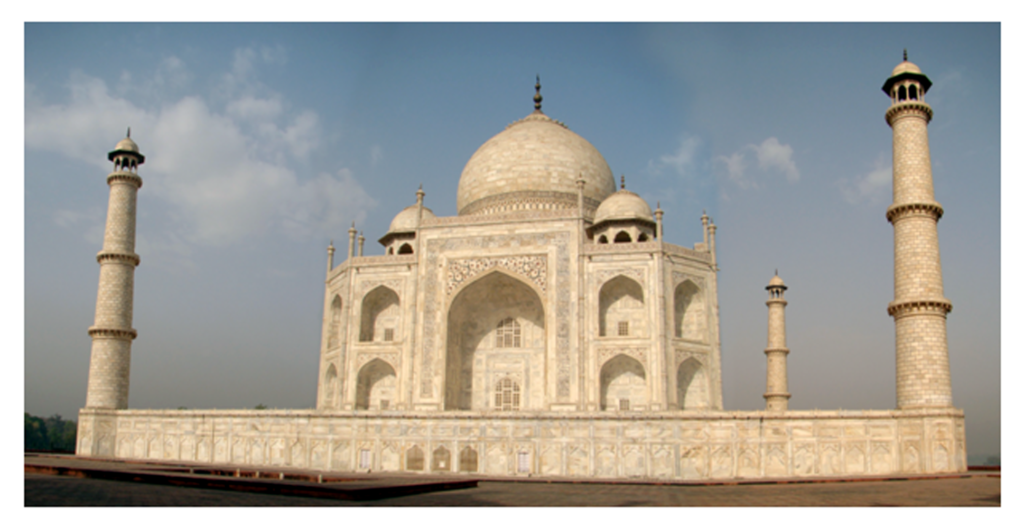

A view of the Taj from the east

The Mughal empire had pretty much stabilized by the time of Shah Jahan, so widely known for Taj Mahal, although the conquests of southern kingdoms remained inconclusive. Just as he had ascended to the throne in a bloody contest, his son, Aurangzeb assumed power having ordered the killing of three of his brothers. His long 40? Year reign was marked by constant warfare. Although he has been maligned by numerous historians for his alleged bigotry and promotion of orthodox Islam, he also has many defenders among respected scholars.

In terms of gender relations, or rather in the way Mughal women were treated by their men, the picture seems quite a bit different from other societies of the time. While segregation of the sexes was strict, Mughal princesses had the freedom to go horseback riding, engage in archery and shooting for game in the forests, all this under the watchful eyes of an army of eunuchs. (The picture about eunuchs, too, was mixed because some of them commanded armies or wielded real power from the shadows of weak sovereigns. The use of eunuchs in royal palaces had been the norm for centuries for all empires from Beijing to Istanbul.)

All across the Subcontinent, people remember the Mughals mainly for two things: Taj Mahal and Anarkali, one an emperor’s monument to his love for his queen, the other a totally fabricated story of love between a prince and a dancing girl who pays for it with her life. The Anakali story, based on a rumor recorded by a foreign visitor to the royal court, was spun into a play by Imtiaz Ali Taj in 1938; it gained credence because a building dating from the Mughal times in Lahore was believed to house the grave of the dancing girl, Meherunnisa. The playwright made no claim to historical authenticity, but no matter, the Bombay film industry produced a film in 1953 that became a major hit, especially because it had several haunting songs that remain the classics of the film-music industry to this day.

In 1960, a remake of the Anarkali story titled Mughal-e Azam, or the Great Mughal, became an ever bigger hit all across India. Its colorized version was released in theaters in the 1990s and later in DVD to great commercial success, which owed partly to the lead roles played by the top actors of the time. . It would be only a slight exaggeration to say that Mughal-e Azam was the Indian equivalent of Gone With the Wind in terms of a people getting a sense of the historical moment.

Basically, the film story was that the prince Salim, who became emperor Jahangir later, falls in love with the dancing girl. They exchange letters, and one day while performing for the royal court, she gets a bit carried away, possibly under the influence of a drink or a narcotic, and makes bold gestures of love toward the attending prince. The emperor, Akbar, gets wind of it, and decides it’s too scandalous to allow his son to marry her, and orders her death, by having her entombed in a wall. End of story.

It always bothered me that nobody cared whether the story had any basis in history, or that nobody would make a moral judgment about the inhumanity of Akbar’s decision. Perhaps the story was too good to be confused with facts, or that people who grew up on the strange, often unjustifiable actions of the hero in the great Indian epic Mahabharta just didn’t care to make moral judgments. Another thing that bothered me was that the story of a heroic woman behind the same emperor Jahangir didn’t get as much play in the media or literature as it deserved. This was the story of Nur Jahan, or Mihirunnisa, the girl born to her Persian parents, Ghyas Baig and Asmat Begum, on their way to the Mughal capital of Agra, and rose to share Jahangir’s imperial powers.

The year was 1581 when her mother gave birth to her in a tent near Kandahar, as their caravan slogged its way through the dusty, bandit-infested highways to Agra. Ghyas Baig, a talented man with high educational achievements, found employment in Akbar’s court where he quickly rose in esteem of the upper levels of administrators. He raised his family of two sons and two daughters in much comfort, giving them an education in the arts and literature of the time as well as a familiarity with the affairs of the kingdom.

For several years Ghyas Beg served as Akbar’s representative in Kandahar, now in Afghanistan, but a Mughal province then. While there he may have met Ali Quli, a young Persian soldier fleeing from the turbulent politics of the Persian royal court, and helped him obtain a commander’s position with the Mughal army then engaged in the conquest of Multan. Ali Quli distinguished himself in those battles and came to Agra with the victorious army, won royal favor and a title. In 1594, when Mihirunnisa was about 17 years old, she was married to Ali Quli, his Persian background and high rank must have been viewed as meritorious enough to win the hand of the Persian beauty. Ali Quli served on Jahangir’s staff during a campaign against Mewar, where, Jahangir rewarded him with the title of Sher Afgan or tiger slayer.

They had a daughter together. In Agra, Mihir went to work as an assistant to the leading member of the royal harem, or seraglio, as English writers have referred to the palace complex occupied by royal women. The historical record is unclear whether Mihir was with Sher Afgan when he was posted to Bengal shortly after their marriage. Power politics took a bad turn in the province with the appointment of a new governor and Sher Afgan ended up in opposition to him. A fight ensued, leading to the death of the young officer. Mihir returned to Agra and resumed her duties in the royal harem

In 1611, when she was 34, Jahangir met Mihir at a bazaar organized by merchants strictly for the ladies of the royal court and the princes. Jahangir married her, and it didn’t take Mihir long to become the emperor’s most trusted and intimate advisor on all policy matters. Jahangir, in thrall of Mihir’s beauty, intelligence, artistic talents and education, first gave her the title of Nur Mahal, or the light of the palace, then the title of Nur Jahan, light of the world. Her father, Ghias Beg, had become the chief administrator of the realm, earning the title of Etimadud Dowla. Nur Jahan’s elder brother, Mirza Abul Hasan, also won appointment to the high office of master of the royal household, and won the title, of Asaf Khan. Both father and son were able administrators, controlling the finances in minute details.

Jahangir, who himself had come to power after mounting an abortive rebellion against his father, Akbar, in his last years, faced a revolt by his own son Khusrow; Akbar had encouraged Khusrow’s ambitions in efforts to stave off Jahangir’s bid to overthrow the emperor. Jahangir’s third son, Khurram, later to become Shah Jahan of the Taj fame, ruled the Deccan in the south. On Jahangir’s accession to power, Khusrow fled Agra to Lahore where he gathered a force of 12,000 and the support of many religious leaders aiming to challenge the Mughal emperor. Jahangir personally marched to Lahore at the head of an army and easily defeated the rebel son, had him imprisoned for a while, then had him blinded to prevent any future challenges to his power. In 1612, Khurram married Asaf Khan’s daughter, Nur Jahan’s niece, Arjumand Banu, who was later to become Mumtaz Mahal.

Thus, barely a year after becoming the queen – she was supposedly the 20th wife of the emperor — Nur Jahan began to assume executive powers, supported as team members by her father, her brother and by Prince Khurram. The prince engaged in major military operations to pacify the kingdom of Ahmednagar that had already been conquered by Akbar and had begun resisting the Mughals. Jahangir spent five and half years in Gujarat, overseeing the control of the key province. When he returned to Agra, his health began to deteriorate and he delegated all his duties to Nur Jahan.

The queen signed off on all royal proclamations, or firmans, along with the emperor, elevated or demoted royal officers, heard petitions and pronounced judgments in major disputes. A definitive demonstration of her power was to order coins to be struck in her name on one side and the image of Jahangir on the other. Inevitably, her direct exercise of power gave rise to rivalry among the courtiers and governors, chief among whom was an old Jahangir loyalist, Mahabat Khan, who was governing Kandahar and Kabul. In the royal palace, too, factions were busy intriguing against her, or spreading rumors and praying for her downfall.

As Jahangir withdrew from active governing, he spent his days in elaborate court ceremonies designed to affirm the loyalties of his key administrators, courtiers and generals. Away from the capital, Khurram became restless looking forward to the day he’d succeed his father, and began taking overt actions to declare his resolve to become the emperor. These actions caused Nur Jahan to make a decision that was to lead to an uncontrollable set of events: Because there was no way for her to succeed Jahangir in the event of his death, she arranged the marriage of her daughter, Ladli Begum, to Jahangir’s third son, Shahryar; her plan, not lost on anyone, least of all on Khurram, was to continue her rule through a weak-willed Shahryar. The move made her break with Khurram irreparable. To simplify matters Khurram took care of his brother, Khusrow’s, a potential contender for the throne although the prince was Khurram’s custody; his death was attributed to a sudden illness.

Now Khurram was fully engaged in a battle of wits, arms and the loyalties of Mughal generals with Nur Jahan who was acting through an ailing Jahangir. Khurram defied royal orders to lead an army retake Kandahar recently lost to the Iranians. Instead, he led an army to take on Jahangir’s forces in Agra. Nur Jahan ordered the powerful and trusted general Mahabat Khan then at Kabul to mobilize and come to the defense of the realm. The general equivocated – he had been openly critical of Jahangir for delegating his powers to Nur Jahan, and saw no advantage in siding with an ailing emperor against an accomplished commander who had a legitimate claim to the throne. He needed persuasion and Nur Jahan maneuvered him into coming on board with the loyalists.

Khurram’s forces clashed with the loyalists in many places, the battles see-sawed, and the civil war went on for three years, causing huge losses in men and materiel. The loyalists maintained the upper hand. Eventually, Khurram gave up and returned to the south. Jahangir took off for Kashmir from where he and Nur Jahan issued orders to control Mahabat Khan, who was now posing a threat to her powers. Both made carefully planned moves against each other. When the royal court moved down from Kashmir toward Lahore, on way to Kabul, Mahabat Khan made his move. Using 4,000 Rajput soldiers and 2,000 Mughals, Mahabat Khan laid a trap for Jahangir on the banks of the Jhelum river.

Once the army of royal attendants had crossed the river, and waited for the emperor to follow, the general took control of the royal camp, in effect holding Jahangir prisoner. Nur Jahan, disguised as an ordinary soldier and accompanied by an assistant, crossed the river to reach Asaf Khan, her brother and keeper of the royal household, and other nobles to give them a tongue-lashing and ordering them to re-cross the river and rescue the king. But they were unable to ford the river at any point, and seeing their lives and positions in danger, both Asaf Khan and a group of nobles took off in different directions in search of safety.

Nur Jahan crossed the river and, in effect, surrendered to Mahabat Khan, who allowed her to live with the emperor. Now Mahabat Khan took the reins of government, issuing orders to the escaped nobles, including Asaf Khan, and other functionaries, who had no choice but to submit. But the simple, straight-dealing general, absolutely loyal to the king, had no plans to declare himself king. All he wanted was to free Jahangir from the influence of Nur Jahan and her brother. The man was no match for Nur Jahan’s strategic thinking and tactical planning. Likely on her direction, Jahangir asked Mahabat Khan to let him review the troops in formation.

At that moment, Jahangir took command of the troops, playing on their loyalty to the king, and at once he was free from restraints imposed by Mahabat Khan. The general knew he had been outmaneuvered, and he fled from the scene toward Multan. Nur Jahan once again took control of the government. This was in August 1626. About six months later, Jahangir and his royal court left for Kashmir, where his asthma and other ailments grew worse. On October 29, 1627, Jahangir died. He was 60 years of age, having ruled as emperor for 22 years.

Asaf Khan, always a quiet partisan of Khurram, sent emissaries to Khurram with the news of Jahangir’s death. Nur Jahan made an effort to get Shahryar to prepare for war with Khurram, and tried in vain to have her brother Asaf Khan arrested. All was lost for Nur Jahan. Khurram immediately set off for Agra and proclaimed himself emperor. To his credit, Khurram, now titled Shah Jahan, allowed Nur Jahan to live in peace in a palace in Lahore, where she lived to age 70.

Three novels[1] have been published in the last 100 years based on the life and times of Nur Jahan. My favorite, titled Nur Mahal, was written by Harold Lamb and published in 1932 by Doubleday. Lamb wrote in an author’s note that “this narrative is the truth . . . The chief characters and the events of the narrative are also historical.”

In one particularly evocative chapter Lamb sketches out the scene, on the banks of the mighty Jhelum where the royal camp with its thousands of soldiers and functionaries had halted some distance from Lahore. While a seriously ill, asthmatic Jahangir lounged in his bed, his mind addled with opium and wine, Nur Jahan assessed the dire military situation. A rebellious Khurram was marching toward Agra at the head of an experienced army. Only Mahabat Khan who commanded the loyalty of the Rajputs and other powerful Mughal leaders could effectively fight off Khurram. She needed Mahabat on her side.

The old Afghan commander had arrived with a large force and was to present himself before Jahangir. Nur Jahan desperately wanted to meet with him in person and offer him enough enticements to take the field on her side. This was something she could not do because the court etiquette and protocol did not allow a face-to-face interaction between the queen and any Mughal officer. So, she donned an ordinary soldier’s uniform and accompanied by an assistant rode horseback to Mahabat Khan’s camp and lay in wait for him to be out in the open.

Lamb writes that Nur Jahan realized she she had a very slim chance to turn things around. Soldiers on horseback moved around in the mud as a torch flared on the far bank. A group of men in gray felt burkas galloped down a sand bar by the ford, speaking Pushtu of the hills.

She climbed back into her saddle and urged her horse across the path of this posse. The troopers reined in, peered at her astonished, and a voice from the cavalcade mocked her: Nur Jahan recognized Mahabat by his black beard under the hood as he rode past, and called his name, that was not known in India.: “O son of Ghiyar Beg! Mahabat Khan stopped in his track and rode toward her, thinking a beggar from old times had called out. She responded qucikcly, saying she was sent by the queen to talk to him. The Khan says he would talk to the queen but not to her messenger, and turns away.

Nur Jahan calls out: ‘You were not in such haste to leave me at the Bihar sarai when the talk was of the treacheryt of Malik Ambar, and you tossed dice with the mullah.’ Mahabat Khan recalls the incident and is confused. Nur Jahan reveals herself.

By the end of their meeting, Nur Jahan had Mahabat Khan on her side, although she had to agree to many of his conditions, one of which was to transfer to Bengal her brother Asif Khan, a Khurram partisan whose daughter was the prince’s wife and potentially the future queen. The general proved as good as his word, and did successfully fight off the rebellious prince. But this was not the last time Nur Jahan locked horns with Mahabat Khan. His capture of Jahangir and keeping him hostage while exercising authority still lay ahead.

Mohammed Mujeeb, in his wide-ranging survey Indian Muslim culture[2], says of the Jahangir-Nur Jahan partnership that “though different from each other in many ways” the two “are an example of understanding and companionship which is rarte even among those who do not fact the ordeal of being surrounded by courtiers and sitting upon a throne.”

Ellison Banks Findley[3] has a more nuanced take on this much fabled royal couple’s relationship. She wrote: “While (in the) traditional Christian models the primal tie of women was to their children, in Hinduism it was to their husbands. The preeminence of the consort in an Indian woman’s vision of her self became complicated in Nur Jahan’s case” . . . With Jahangir, Nur Jahan was not only the marriage partner supreme, but also one who had to praise and scold, nurse and protect as well. The tradition would see in her, then, the consort ideal broken wide open, testing strengths and emotions hitherto devalued.”

Most historians, particularly the European travelers of the time, were dazzled by the power Nur Jahan exercised, but Professor Mujeeb is among the few who noted the lasting influence Nur Jahan has had on Indian culture. For example, the bridal clothes and jewelry worn to this day, at least among the Muslims, are believed to have been originally designed by her. Mujeeb wrote in a footnote: Nur Jahan is believed to have introduced the custom of using white cloth for spreading on the floor because carpets were expensive, and people who could not afford them could thus safeguard their respectability. The white cloth, called chaandni (moonlight), became the fashion and is still used. It is generally spread over a cheap carpet or mattress of some kind.”

[1] The other two fictional accounts are Nur Jahan: A historical novel of Mughal India by Jyoti Jafa. Calcutta: A Writers Workshop Publication, 1978, and The Twentieth Wife: a novel by Indu Sundaresan. New York. Washington Square Press. 2003.

[2] P361, The Indian Muslims:, M. Mujeeb, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1967.

[3] P5, Nur Jahan, Empress of Mughal India, OUP New Delhi 2000.