The taste of frozen Indian jaamun found unexpectedly in a grocery store brought to mind the long lines of jaamun trees along Hyderabad’s University Road. During the summer, the trees were loaded with the purple fruit, which, toward the end of the season, dropped to the ground and made it a patchwork of black and purple. Who could resist reaching up to the low-hanging jaamun and grab a few? Neighborhood boys filled their pockets and stomachs with them, having picked them by climbing the trees. My younger brother and friends from our street would be among them, perhaps until around age 10 or 12.

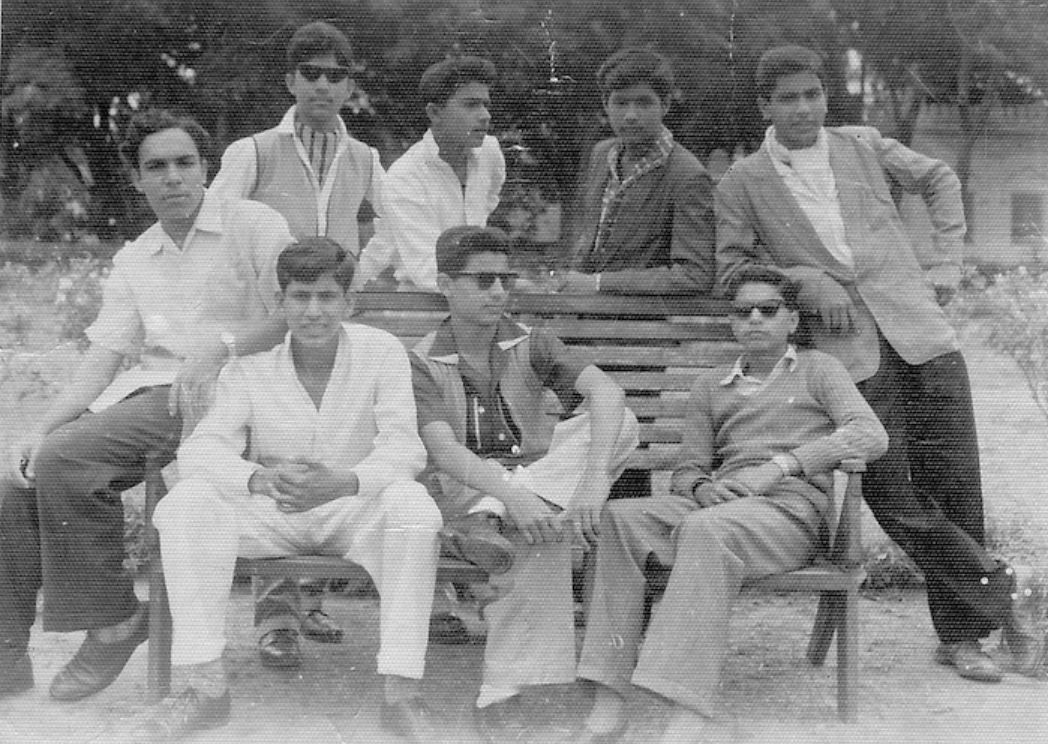

During the winter months, the jaamun trees were host to large bats that hung from the branches. They must have measured a foot or more from their claws to their heads dangling upside down, especially near the top of the hill near the library. There were many nights when I got off my bicycle at this hill and just walked, returning from downtown Abids or the Tank Bund where friends from Madars-i-Aliya, Grammar School or Anwarul Uloom College hung out, a year or two after graduating from high school. This must have been during 1960-62. The excited talk among these friends at that time usually focused on “pushing off” out of India. Everyone was just waiting for “the call,” the bulaawa, from a brother or sister or uncle, somebody. When it came through, they’d be getting the hell out of here. The destinations we had in mind were England, the Gulf Sheikhdoms or at least Pakistan. A rare few among us looked forward to going to America.

But as it happened, many of us ended up in America or Canada. For some, their journeys took them first to Pakistan, then to the Gulf, and then to North America. Some, of course, ended up in Australia, the least desirable of the destinations, in my opinion, but it sure beat staying behind in Pakistan, or India for that matter.

Some friends from that time moved on to a world beyond time. Among them was my childhood buddy, Ikram Ahsan, one of five sons of Professor Mohammed Ahsan. I had known since the primary school and Aliya. Our friendship had renewed after his family moved from Mallepally to the University Road, near where I lived. We took many walks together along the University Road, plotting our departure from India on a motorcycle via Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey and on to Germany or England. In actual fact, I left India aboard a ship from Bombay that dropped me at Busra and I took the fabled Orient Express to Istanbul and across Europe to Munich where I landed, and spent a couple years, before arriving in the United States, in 1972. Three months after I left, Ikram went to Pakistan and then took trains and buses to Istanbul where he caught the train and ended up in Berlin. Shortly thereafter he moved to Iceland and then to Sweden, where he got married to an Icelandic woman. He had two children by her before divorcing. He married again, and had two more children. Ikram Ahsan died in 1995 of a heart attack. He was barely 55.

Among the other friends from school who passed away was Hasan Askari. Askari was the most popular among my Aliya friends. He was the stepbrother of a famous architect (I can’t recall his name) whose wife was popularly known in Hyderabad as “Madhubala”.

Askari’s closest friend was Ali Zaheer, who also passed away, in 2013, at age 65. Zaheer was among the few of us who had achieved some kind of all-India fame as an Urdu poet. He had published at least five collections of poetry, and presented some literary shows for an Urdu television channel.

One of Zaheer’s closest friends from Aliya was Zainul Abedeen, who had played at the state level in cricket, worked for an Indian bank, and moved to the Emirates, where his wife was a schoolteacher. When I met him in 2004, he had recently moved back to Hyderabad to retire. He died of a stroke in 2005. One of his cousins, who also had returned from Saudi to retire in Hyderabad, was Mohammed Hamid Ali. In class V and VI, Hamid had the distinction of shooting his “dhaar” above the wall of an enclosed space designed to serve as a urinal in Aliya. The walls must have been at least 6 feet high. He was doing fine when I last saw him in 2007 in Hyderabad.

Qamar Ali Yar Khan, a CC member, was part of the same Aliya group sort of headed by Askari, and Qamar must be one of the most professionally successful of our group. He is a CA, in Chicago, I believe.

Another one who achieved some success was Habibur Rehman. He became a top executive of Oberoi or some such national hotel chain. The story I heard about him was that he was serving in the Indian army as a captain, working closely with a major who had two small children and lived nearby, when Habib and the major’s wife fell in love with each other. The major divorced his wife and went away. Habib married her. Another story involving Habib was that Askari sat clutching his resume outside the Oberoi conference room where Habib was holding a staff meeting. Askari was hoping to land a job at the hotel chain. An office orderly told him the boss had nothing to offer him and he went home empty-handed. Poor guy had been dead a few years when I was visiting Hyderabad in 2004. He was buried at the Yousufain. The shrine’s head, Faisal, was a close friend of his.

Among the Grammar school guys I knew was Faseeh, who, I understand, died a few years ago in Canada. I briefly knew “Sheru”, the son of Col. Amir Ali of Tableeghi Jamaat fame, while we were at Anwarul Uloom in 1961-62. Shamim Ahmed, the brother of Naseem Ahmed, is another one I have known a long time. He lives on Long Island, NY.

In our diaspora, we have made many kinds of adaptations to the Western environment. A self-imposed isolation from the American and Canadian societies is one choice made by some families in which niqaab is worn by women. In other families, headscarves are preferred by some women; just plain modest dressing is the choice of many others, many of whom hold professional jobs. Some of our children have married outside the community, and the divorce rates seem to be what they are in Hyderabad itself, although no statistics of any kind are available.

Whatever our experience of immigration may have been, it seems important to record it, if only for the sake of our children and their children in order to keep the memories alive as long as possible.