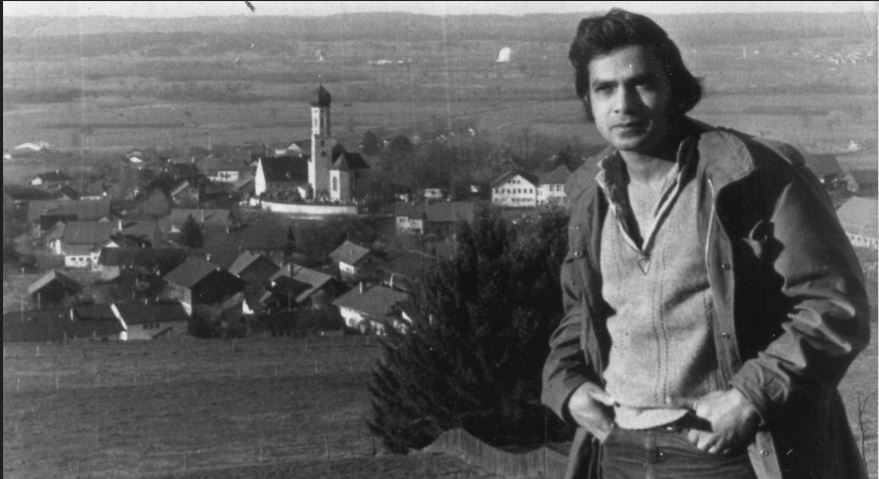

Thousands of young backpackers streamed through the Munich youth hostel during 1970-71

when I worked there as one of a handful of staff checking in young people of various

nationalities, Americans mostly, for a three nights’ stay during the tourist season. This was

where my life as a bum turned around, crossed the Atlantic and spent 53 years in quest of . . .

something.

At 26, I may have been a year or two older than these long-haired traveling whom I had first

encountered a few months earlier in Delhi, where I had been working as an entry-level copy

editor at an English newspaper called Patriot. Time and Newsweek magazines were running

breathless cover stories not just about the draft resistance, but also about the “ravages of

affluence;” they wrote that it was considered totally gauche on elite college campuses to

speak of any ambition to accomplish anything in the business world. A Harvard senior was

quoted as saying that he just wanted to drive a taxi all his life.

One of the first places in Munich these travelers hit was the Hofbrauhaus, the 400-year-old

beerhall among whose clients at one time was Lenin, and the place wasn’t too far from

Burgerbraukeller, one of the largest beer halls from where Hitler and his gang launched the

Beer Hall Putsch of November 9, 1923.

My own favorite was the Mathaser, a block or so from the Haupt Bahnhof, the main train

station, where, for the price of a round of beers for the live band, you could conduct it, and

have the members play “Es gibt kein beer auf Hawaii, Ich fahre nicht nach Hawaii (There’s no

beer on Hawaii, I won’t travel to Hawaii.) The bahnhof was also where an all-night beer hall

served as a night-long refuge for stranded souls, mostly men, mostly foreigners, served by

strong middle-aged German women who scolded patrons who were dozing off, “Kein

schlaffen! Kein schlaffen”! no sleeping, no sleeping — it’s a beerhall, not a flophouse for derelicts.

At the Munich Jugendherberge, the youth hostel, many of the travelers gathered at a Pizza

Hut that also doubled as a full-fledged bar on the nearby Wendell-Dietrich Strasse. The joint

came alive when the music played the Beatles’ “Come Together”, or Janis Joplin’s “Nothing

left to lose.” I was having a beer one afternoon with two Australian women who had just

come off a trip through India. They asked me just why was there so much poverty in that

country? “Why don’t they just build more houses and roads and things for the people?” they

asked. I mumbled something about resources; but what I really should have said was: If I

had the answer, Ladies, would I be an illegal guest worker in Germany? I had quit a

professional job because the measly salary it paid was not enough to send money home to

help father support our family of seven members. But with a hostel clerk’s day job in Munich

and a second job as a waiter, I could even save some.

I also remember another conversation, with a woman from San Bernardino, CA, who

wondered, admiringly, how people from my part of the world seemed to her to be so content

within their skins, no self-doubt whatsoever, no sign of any existential angst. Apparently, it

didn’t occur to her that the people she was talking about may have had more immediate

concerns about keeping body and soul together.

In any case, Americans were the easiest to be friends with, and it was not just because of the

English language common between us. Lots of Brits, Irish and Aussies also came through the

hostel. It was because they were so non-judgmental about me or the other Asians and

Africans who worked or stayed there. The feeling was shared by Sameeh, a Pakistani

Punjabi, and Meinu, a Bihari from what became Bangladesh, who worked in the hostel’s

cafeteria. We were in the same boat regarding our visa status, and we knew that unlike most

of the hostel guests we weren’t there for fun and games. We were there for the serious

business of working and sending money home. We were desperate to find a permanent and

legal situation somewhere for ourselves, and we harbored a nagging sense of inferiority vis a

vis the traveling folks. We appreciated the Americans’ not looking at us through the filter of

our respective nationalities, or place us in other insulting categories the way the visiting

Europeans did, or so we thought. Sitting around one day, I mentioned to them the day’s news

of four Germans getting killed in a train accident. Meinu said, “Really? It’s sad. But you think

we can apply to take their places”? Sameeh said, “We’ll promise we’ll be just as good as

them, just as hard working.”

Some people hung out in the cafeteria even if they were not staying at the hostel, their eyes

surveying diners finishing up their meals with some food still on their plates. As they got up,

the hungry ones jumped up to take the plates away from them. I got to know some of them

as they hung out in the park across from the hostel, throwing Frisbees or gathering around

some guitar players and singers. Among them was Barry Nord, 25, from Philadelphia. He

was a teacher at a junior high when he dropped out and took to the road. He possessed

nothing more than a sleeping bag and a few books, which he hid in a nearby cemetery, and

hung out in the park. What little money he had came from breaking into vending machines.

“Think of all the money you have lost over the years,” he told me. How long would he go on

like this? I asked. “As long as it is fun,” he said, leaving me to puzzle over this kind of attitude

to life.

Joan Cabot, 22, from Silver Spring, MD, was traveling alone and not very happy about it. She

had recently broken up with her boyfriend and just quit her job and took off for Europe.

Apparently, she had been “doing drugs,” whatever that meant. “Oh, doing everything, like

acid, buttons, some hash and, of course, pot.” I was getting an education of middle class

American life. Cabot had been working as a legal secretary and living with her parents, and

had saved a tidy amount. Her friends encouraged her to go to Europe “like everyone was

doing it.” She quit her job and hopped on to an Icelandic Airlines flight that cost a roundtrip

fare of $220 and landed her in Luxembourg. She bought a Eurail pass that allowed her

unlimited travel in Europe for two weeks.

Whenever I received letters from home, my original self asserted itself. The Bangladesh war

had crippled the Indian economy. The money I was sending helped, but the two college going

brothers each had no more than one pair of pants and a shirt to wear, and father struggled to

pay their tuition and bus transportation. Worse, job prospects were zilch for them and their

friends. I myself wondered how long I could go on in my precarious, illegal worker status.

During the winter, a young New York guy came to work in the front office. The hostel was

mostly deserted. One day Joe, his Austrian girlfriend, Grada, who also worked at the hostel,

took Sameeh, Meinu and I skating with them. At the rink, we rented the shoes and watched in

amazement at families skating together, gorgeous girls in tights whizzing by. We got on to the

rink and stood clutching the railings, keeping our balance. We kept falling at every attempt we

made to skate, and burst out laughing. “Look at us grown men, acting like children, falling

down like children, as if we had not a care in the world. Would we ever do such a thing back

home? Enough of this stupidity, already.”

Another winter day, Joe and Grada took us to an indoor, heated swimming pool. The sight of

young lasses in their skimpy swimsuits was right out of our wet dreams, never having seen

even a picture of a nude, all three of us having attended all-boys schools in our respective

countries. Here at the swimming pool, transfixed, we stared at them, finding it really, truly

hard, to get out of the pool when Joe motioned to us. It was too damn embarrassing to be

coming out with a hard-on. Eventually, Meinu got out, gave us towels with which to cover

ourselves.

An uncle finishing up his medical residency in Omaha encouraged me to apply to US colleges

and promised to help pay the tuition. Within months I landed at Columbia, MO, enrolled at the

local university’s journalism school. On campus, it was hard to find the kind of young

Americans I was familiar with. Transcendental Meditation was big, as was something called

the Eckanker group, folks who were looking for “the light and sound of God” through their

spiritual practices. I was looking for people who found the world as exciting as I did, and not

overly inward looking. One place I found them was the daily vigil against the Vietnam war,

where 10 to 20 people stood in a line holding placards. I met a nice couple there, Julian Will

and Naomi Schneider, both recently returned Peace Corps volunteers and both enrolled in

graduate social work programs. They had friends dropping by at their apartment all the time

and having impromptu pot-smoking parties. All of them aspired to making a living totally

independent from the corporate system. Judy and Mark ran a vegetarian restaurant and a

small bookstore promoting an alternative lifestyle. Bob and Kevin dreamed of owning a farm

and raising organically grown crops. Some thought it was strange and unusual that I would

be looking for a job in the newspaper business.

The civil rights movement was in full swing, and thanks to it, I found a reporter’s job at a daily

newspaper in a small town on the Kansas side of the Oklahoma border – the newspaper

management, like many of its kind, were beginning to think about hiring from among the racial

minorities. A Vietnam war veteran running the news bureau at the Arkansas City (KS)

Traveler found me close enough to what he was looking for. The town sat a few miles from

where the line was formed for the 1993 Cherokee Strip Land Run in which some 8 million

acres were up for grab. Two museums, one in Perry, OK, and the other in Arkansas City, KS,

display large pictures of the line that was formed for the run. One picture that sticks in my

mind shows men in suits with a sign dangling from their necks announcing that they were

attorneys at law, ready to record the stakes people had driven in the ground.

My American avatar was on top of his game, having found a career to pursue and a new

world to explore. The small-town folks were easy to please, especially after I wrote an article

talking about how I came from a town in India, Hyderabad, that gave the world its largest

diamond, the Koh-i-Noor which became part of Britain’s crown jewels, and the Hope

Diamond, now housed in one of the Smithsonian museums. I wrote that the freedoms I had

found in America were more precious than those gems. Everybody lapped it up and no one

thought the lard was a bit too thick.

Fast forward a few years, I was in Oman, serving a two-year Peace Corps stint, making

frequent trips to my old hometown of Hyderabad. With a sister’s help, I found someone, an

English lecturer at a college, to marry and raise a family with in the suburbs of Washington,

DC, the nation’s capital.

A Rope Hanging from the Sky

The chirruping of a bird one early morning near my window triggered a 47-year-old memory

as I sat down in front of the laptop, with a good buzz on, a gooood buzz on, as a rock lyric

had it. It had to do with my six-month stay in Nagpur, in central India, where I had found my

first real job. It was at a daily English newspaper and the year was 1967. I was one of three

sub-editors. Our job was to clean up and put headlines on everything that went into print. The

local reporter had no say in the matter, only the boss, the news editor who was the final

gatekeeper of everything that appeared in the paper. Those six months were a time when I

thought I had caught the rope hanging down from the sky, and I could climb as high as I

wanted or could. I had a job! A professional, journalist job! What more could I want at that

time? Oh, a lot more soon, as it happened.

Having come through a time gripped by poverty, a total void in terms of job or career

prospects because the Indian economy was in the tank because of the China war (1962) (fact

check), the Pakistani raid in Kutch (1963) and the Kashmir war (1965). Doom and gloom as I

graduated from Osmania University’s journalism school at age 24 and spent a month or two

as an unpaid intern at a news agency, except my position was never formalized. The agency

chief, Sita Ram, just told me to come to office and accompany him to his state government

beats, or bring in stories based on leads he would provide. No money to buy an extra shirt or

a pair of new pants. I rented a bicycle by the hour to go downtown or to the news agency

office, 10 miles from home. Father close to retirement, and weak in health, two unmarried

sisters, one a year older than I at 25 and the other 19 or so, and four younger brothers, none

doing very well in school. Uncle Sajid, 5 years older, had graduated with a bachelor’s in

engineering, his newly wed wife was just finished with medical school training. Neither had

any job offers. Out of the blue, literally, this subeditor job materialized when my journalism

professor recommended me and a classmate, D.K. Vishwanatha Rao, to the newspaper

publisher. Within days, I was on my way.

For the next weeks and months, I woke up from bed, feeling how exhilarating! how exciting! to

find myself a “working journalist,” in the lingo of the much respected profession at the time.

Again, I rented a bicycle to commute to work six miles away. The monthly rental was Rs. 30

when it cost Rs. 150 to buy it outright , 40 less than the monthly salary, or remuneration as it

was called since the colonial days. I had rented a room for Rs. 60 and was paying an equal

amount to have two meals delivered. Other rooms at the place were rented by young men

who attended a pharmacy school or had jobs, maybe six of them altogether.

Nagpur had been the capital of British India’s Central Province, which came to be called Madhya Pradesh in independent India, but the city became part of the Marathi-speaking Maharashtra state in the country’s reorganization along linguistic lines. Nagpur had a military base, except it was called a cantonment area where troops were housed, and there was a residential area called Civil Lines where the British Indian gentry lived. Two English newspapers served the city: The Nagpur Times, with a circulation of 30,000 and the Hitavada, where I worked, circulation about 11,000. Both had a few Anglo-Indian men on their staffs.

Some of these folks were coastal Catholic Christian Goans, too, which made sense since the former Portuguese colony was only a couple hundred miles away. They spoke English, and my comfort level with English plus college graduate status gave me a sense of confidence vis a vis the other staff members, some of whom were Marathi speaking Hindus. The news department chief certainly was one because he was a Brahmin, wore traditional priestly clothes and had the red mark of Brahminhood adorning his forehead. He commanded an extra dose of deference and affection from lesser mortals around him. The man walked barefoot in the office, for some reason, but he indulged himself with paan-chewing, seemed to love the mild narcotic, and he had no problem with my being Muslim, someone out of a totally

Muslim Hyderabadi milieu, having no caste sensitivity or any understanding of the caste-dominated society.

My room shared a wall with a daycare center or some kind of Christian, English-only, preschool probably run by a Christian Missionary-trained teacher. For, this ghostly being whom I never met led her class in singing English nursery rhymes. “The farmer had a wife, the farmer had a wife, hi-ho, derry-o, the farmer had a wife,” or some such thing. I do remember more distinctly “the mulberry bush”. Day after day I awoke mostly to the same damn nursery songs sung by a chorus of full-throated preschoolers. The class, of course, began everyday with a singsong “Good morning, teacher”, followed by “Good morning, class.”

Working hours were 4 p.m. to 10 p.m. six days a week. All morning was available for staying in bed, curled up with a book. The newspaper office had a small, dusty room that housed a library, books mostly received for reviews or donated by friends. I found an autobiography, “My Wicked, Wicked Days” by Errol Flynn, the Hollywood actor of whom I had never heard. Flynn was an Australian man, a professor’s son, who dropped out of high school, ran away from home, worked at odd jobs, and got hired by a theatrical company visiting from London.

Performances at the London theater lead to his discovery by a talent scout representing a Hollywood studio. Young 6-feet-four Errol Flynn, a handsome and strongly built lad, becomes America’s heartthrob overnight, with his swashbuckling roles as Captain Blood, . . . and other pirate films. One sex scandal after another was his fate over the years he dominated the scene, mostly charges of rape, statutory or otherwise, all of which Errol Flynn seems to explain away as exaggerated, or envy or media frenzy.

Errol Flynn’s story lit up my imagination, and blasted my ambitions into the stratosphere, but there was no way to fly to London or New York. After six months in Nagpur, I was hired by New Delhi’s Patriot newspaper, a Soviet-funded daily staffed mostly by South Indians, as was much of India’s English journalism because of the Southerners’ greater exposure to English under a direct colonial administration, unlike the experience in Hyderabad or other cities that were ruled through princely state heads.

Six hours of work from 8:00 p.m. to 2 a.m. left a lot of time to fill during the day in Delhi. Being driven home in a company car at night was nice, but living in a group home run by a Malayali man was barely acceptable. This somewhat older man also operated a “mess,” which in the Indian parlance meant board for working men, who didn’t necessarily live there. At the Patriot newspaper office, the horseshoe editorial rim was staffed by a mix of South Indians and a few UP men known as Pahaadis, or mountain folk of the Almora and Nainital region in the foothills of the Himalayas. I can never forget the remark made by one of the two copy desk chiefs, Peiynuli Singh, about the mountain men like him. The highest compliment

you could pay a Pahaadi was to say that he didn’t look like a Pahaadi.

Although they invariably were light-skinned and had normal physique, their inferiority complex had to do with their lower educational accomplishments and the general poverty of the region. A lot of them were crowding into Delhi’s job market, which, of course, was a magnet for all regions of the country. Years later I was to learn that Jews in America loved to be identified as anything but Jewish. “Funny, you don’t look Jewish” was a standard joke among them. A Jewish friend in college told me one about a New Yorker visiting Beijing and meeting a Chinese Jew. Yep, the first thing the New Yorker told him was “Funny, you don’t look Jewish.” The protagonist in Erica Jong’s “Fear of Flying” loved it when her married name became Bennett, although the guy was ethnic Chinese.

The Coffee House, located in the center of Delhi’s Connaught Place, which is partly a colonnaded circularly built shopping area, became a crowded haunt for the young professionals of the city, many of them children of the Punjabi refugees from what is now Pakistan, or transplants from the south. Part of the Coffee House was open air, serving wadas and veggie hamburgers or veggie cutlets, and coffee, of course. During 1967-70, it was also where young American and European tourists gathered. Some of them came through in minivans via Afghanistan, some bearing stories of robbery and injury, according to newspaper accounts. Their drug habits did not bother the Delhi authorities, who welcomed all kinds of

Western tourists.