Why did Savarkar / Hindutva turn against Indian syncretism, and India’s march toward modernity?

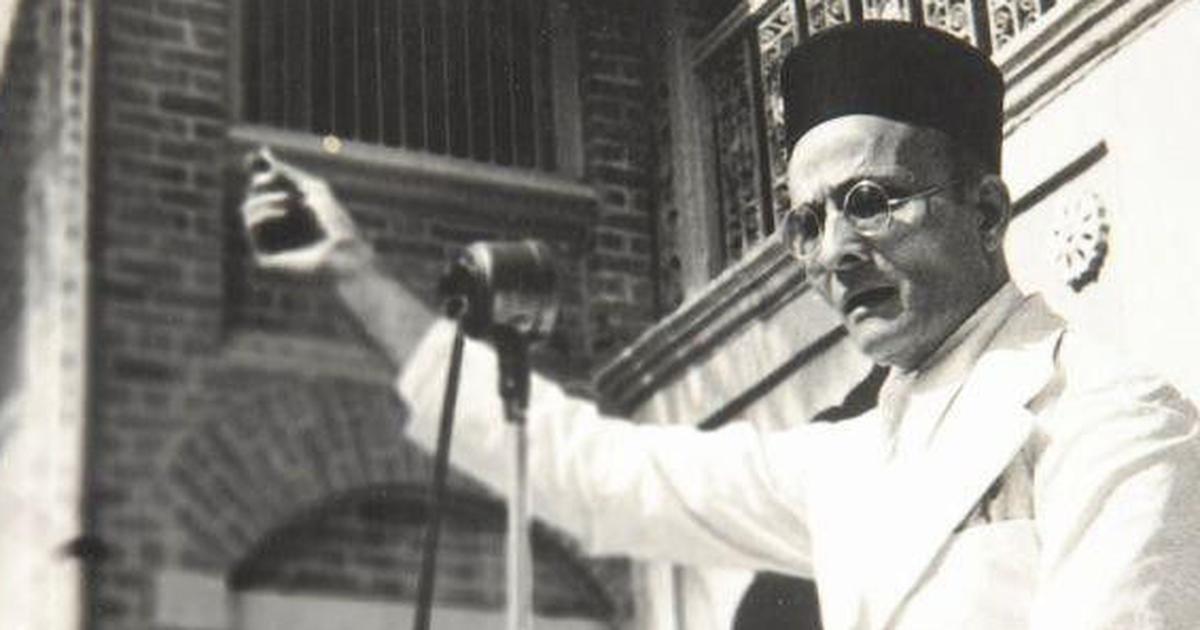

Damodar Vinayak Savarkar’s seminal book “The Essentials of Hindutva” was published in 1923. That was the year Indian Muslim Khilafat agitation was at its peak during its fourth year, 1919-24. The concept of extraterritorial loyalties, and a separate authority proposed by the Indian Muslims for the tottering Ottoman head, Sultan Abdul Majeed, was sobering and shocking for the high caste Hindus. The Muslim dreams and phantasies were focused on nothing less than turning India into a totally Islam-oriented world across the Subcontinent.

The Indians’ interference on his behalf did not sit well with Kemal Pasha Ataturk, who decided to get rid of the khalifa Abdul Majeed at Topkapi, Istanbul. That ended the deluded Khilafat storm in a teacup.

Since the end of World War I, it had become apparent that India would become independent sooner rather than later. Still, the question was which ideological vision would bind a hugely diverse population together? For the Muslims, Mohammed Iqbal had given an ideal of Islam that would be resurgent, free of the British overlordship, and swiftly turn to God. Whose God? Allah, presumably.

Indian scholars and leaders who knew enough about Muslim history were familiar with the concept of Dhimmi in a theoretical Islamic framework. Was it ever invoked in history? I don’t think so, except in the rhetoric of mullahs in the pay of authorities, such as was customary at Cairo’s “Islamic” university, Jamia Azher.

Indian leaders rejected the weird 7th-century formulation of Muslim victors and their non-Muslim subjects. In a way, the four Shankarachariyas representing the four corners of India constituted the Vedas-oriented Hindu orthodoxy. At the time of Independence, the orthodoxy saw the need for accommodating modernity, but not so fast, they’d say. The reformists, M.K. Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Sardar Patel et al, were hellbent on taking India toward an egalitarian, democratic vision of India. The leaders were enlightened enough to invite Ambedkar to write the Indian Constitution. It was a divine moment. Ambedkar’s language was insistently informed by ideas of equal respect of all religions. No promise of freedom FROM a religious designation. Who is a Hindu? It was never defined or settled. Whoever is not a Muslim or Christian was a Hindu. Period.

It was totally ecumenical and in the best syncretic traditions. This was so in spite of Pakistan declaring itself a theocracy or defining itself as an Islamic republic, whatever it meant then or now.

The times were such. The ideas market was filled with constructed or resurrected ideologies. They competed for attention. Parallel constructions and intellectual projects. Abul Ala Maududi stood for one such ideological project, an Islamic state, whose ghost still dominates in the heats of many millions of Arab Syrians, Iraqis, the Taliban, and their Pakistani cousins.

All Islamic ideologies are exclusivist. Savarkar’s ideology was every bit as exclusive as was Maududi’s. Nehru never tired of saying that Hindu communalism feeds off Muslim communalism in a vicious cycle. Read exclusivism for communalism, a vague term.

Savarkar and Maududi could never allow equal space for each other.

Speaking of Maududi, his own seminal idea of an activist Islamic state echoed in Iran’s Imam Khomeini’s heart. He built upon it as a system called wilayat-e faqih, rule by shariah and fiqh. What was to keep such a system of thought from sparking a clear but apparent counter model presented for the non-Muslim majority, or Hindus, Sikhs and others?

“Islam” the way it evolved in its Indian environment was deeply influenced by the best Vedic thought and practices. Muslims basically share the same tolerance of other people’s mythologies as do the Veda-based ones.

Religion-based exclusivism goes against the grain of the Vedic religion.