Muhammed Iqbal, the Indian Subcontinent’s much loved Urdu poet, wrote a stirring poem titled Masjid-e Qurtaba after his visit to Cordova, Spain, in 1933. In the minds of the Urdu-speaking Muslim elites, the 128-line poem served as a summation of general Muslim grief over a sense of downfall from the peaks of civilizational brilliance in Baghdad and Andalus in the medieval centuries.

Muslim elites of north India wholeheartedly embraced that highly romanticized view of lost glory, and made it a part of their self-identity during the 1930s and 1940s. It provided the salve to their wounded self-image, and showed a way possible back to blazing trails in history. The reality was something entirely different. Iqbal’s great religio-political narrative was ahistorical.

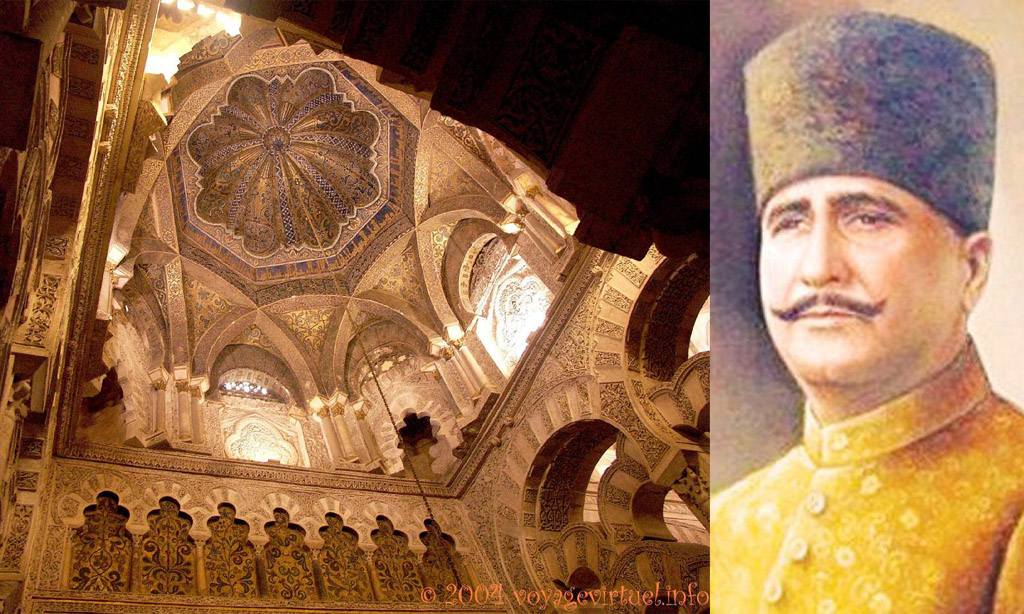

At age 75, although I didn’t care one bit for Iqbal’s Islam-based romanticism, I was drawn to Cordova, Spain, to the place Iqbal called “Masjid-e Qurtaba”, despite the fact that the place had been unrecognizably reconstructed as a Catholic cathedral beginning in 1236. It was time for me to reexamine this part of my Muslim heritage.

In my secular reading of the poem, Iqbal starts out lamenting the evanescence of life, and speaks of a love of the Divine Being, suggesting that such a love had animated the founders of al-Andalus. He points to the wonder that the Qurtuba mosque once was, the crowning monument to that love of the Divine. Iqbal’s vague references to history are counterfactual. Worse, his ideas play into the hands of jihadi extremists and terrorists, from Pakistan and Afghanistan to all the disaffected parts of West Asia and Africa.

In Iqbal’s view, the early founders of the Andalus were men of God, and the brilliance of the Andalusian culture was a result and proof of their godly qualities. In reality, the first conqueror, Abdul Rahman, had created an empire for himself with his Arab and Berber supporters; he built a large Friday mosque that was a grand replica of the Ummayyad mosque in Damascus, which he had seen in his childhood, a homeland he could never return to. Although a victim of bigotry, Abdul Rahman I promoted tolerance,

and pursued a policy of peace and prosperity among the Muslims, Jews and Christians. The result was a burst of energy in all fields of life, from agriculture to industry, arts and scholarship.

A modern reader of Iqbal’s poem would have trouble applying his idea of a “mard-e Khuda” (man of God) to any of the amirs of the city states that dotted Andalusia in the eighth century through the 1230s. These amirs were deeply divided among themselves and fought against one another over territory. The weaker among them sought the help of outside forces, chiefly the Berber kings of Morocco. The Berbers exacted a price and tried to use their Andalusian client states as their colonies, appointing their own

agents and imposing taxes.

One set of the Berber kings, known collectively as the Almoravids (or al-Mirabitoun — the coalition) were conservative and akin to the Saudis oftoday in their hatred of pluralism in society in which races and culturesmixed, the pursuit of happiness was the norm, students flocked to libraries and universities, commerce thrived, and revelers indulged themselves in wine drinking, music and dance. The mullahs raved from the minbars in the mosques.

The destruction of Baghdad at the hands of the Mongol hordes was still a few decades away, when there arose in Morocco and Andalusia an even more conservative set of Muslim fighters who went by the name of Almohads, a corruption of al-Muwahedeen or the Monotheists. They were the Taliban and the ISIS madmen of their times. They were in power in many of the city states when the Christian forces in neighboring states got organized. Pope Innocent goaded the Gauls and the Germans to invade Andalusia. When they attacked, the Almohad Muslims’ defenses crumbled in Saville and environs.

“The generally turbulent religious climate in al-Andalus drastically changed the composition of the Muslim cities,” writes Maria Rosa Menocal, the author of “Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain.”

“A significant flight of the dhimmi, the Jews and Christians who had been a vital part of the vivid and productive cultural mix, now began. Regrettableas all this was, still worse to follow: an even more repressive Berber regime overthrew the Almoravids in North Africa, and kept al-Andalus as its own

colony. The Almohads’ brand of antisecular and religiously intolerant Islam was at irreconcilable odds with many Andalusian traditions Spanish Christian rulers of their city states, who were divided among

themselves, took the help of northern Europeans and won their first victoryover the Muslims in 1212. It was “the clear beginning of the end virtually nothing but Muslim losses and retreats followed this disastrous Almohad defeat. Like dominoes, the grand old cities fell to the Christians one by one:

Cordoba in 1236; Valencia in 1238, and finally Seville, the lovely orange-filled city the Almohads had made their capital.” Were the Almohads the ones who represent the “mard-e Khuda” of Iqbal’s imagination? It’s hard to see anyone else in Andalus fitting that description except the Taliban and ISIS fanatics in their earlier incarnation.

A plausible lesson drawn from a survey of Andalusian history is that the fanaticism of the Almohads, the militant Monotheists, may have been responsible for sparking a much fiercer fanaticism among the Christian kingdoms that reigned supremed after 1492, paving the way for the horrors of Catholic Inquisition.

The story of Andalus’s history shows that religious fanaticism is the enemy of pluralism and multiculturalism as the organizing principle for a peaceful, productive and decent society.

Bigotry begets violence and hate all around.

As for Iqbal’s Masjid-e Qurtuba poem, it is still serving as a powerful tool for the jihadist forces in Pakistan to recruit potential suicide bombers. Take a look at the Youtube films and clips that glorify “Islamic” warriors on horseback, reimagining the conflicts of early Islamic years and giving them, somehow, a contemporary feel, a perception. It’s a blatant call to join the jihad to spread Islam. Iqbal’s poem rolls down the screen to martial music.

There’s much to celebrate in the Andalusian efflorescence, which paved the way for European Renaissance. (Iqbal himself makes a reference to it) But the zealotry of the Muslims helped to kill it. It was not a force for the good, as Iqbal seems to have imagined.

Copyright Usama Khalidi